Beyond Punishment: Switzerland’s Four-Pillar Blueprint for Tackling the Overdose Crisis

This article was was written by Ambika Grover and edited by Swathi Srinivasan as part of The Roads to Recovery. Photography/interviews were conducted in Switzerland by Swathi Srinivasan in July 2024.

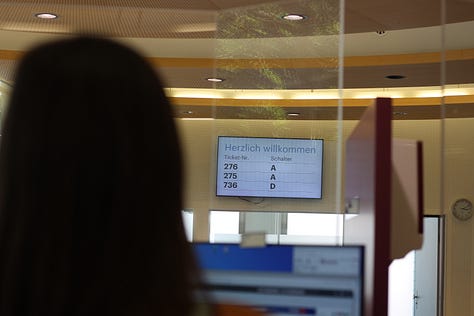

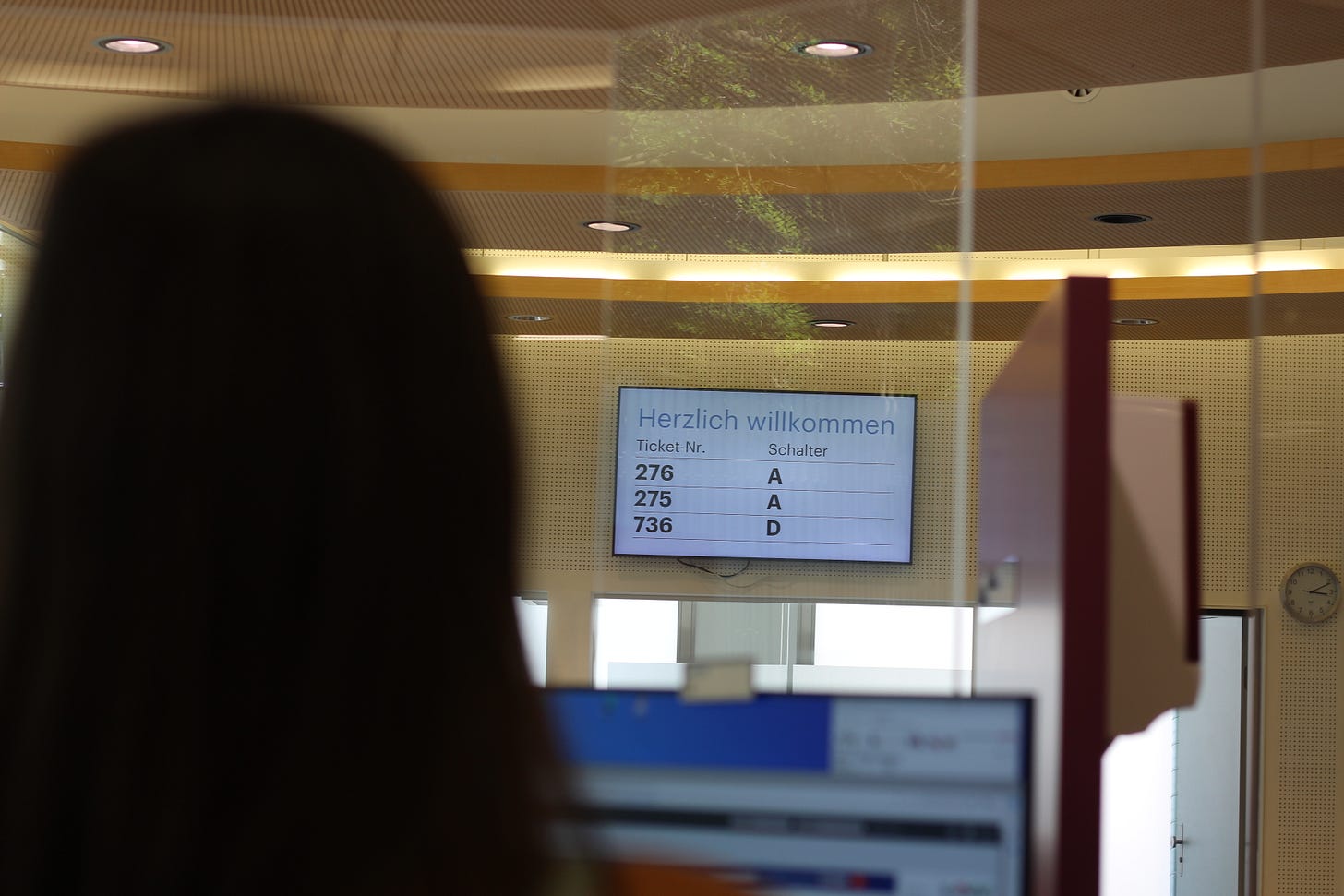

At the Arud Centre for Addiction Medicine in Zurich, clients draw a ticket number and await their turn for medications such as buprenorphine and diamorphine. Switzerland’s take-home programs are one of the hallmarks of its multi-pronged approach to substance use disorder and overdose prevention.

For a country whose yearly drug overdose rate pales in comparison to the United States – under 200, relative to over 100,000 in the United States in 2024 – it is easy to forget that Switzerland had a tumultuous journey to becoming a global leader in harm reduction. A stroll by the infamous Platzspitz Park, situated at the confluence of the pristine Limmat and Sihl rivers, offers a quaint snapshot of a charming city, complete with manicured lawns and idle picnic-goers. But some 30 years ago, Platzspitz Park, often referred to by its nickname “Needle Park,” was the epicenter of an open-air drug scene, drawing in thousands of people using heroin from across Europe to a place where they could use in a de-facto decriminalized environment.

Zurich’s plan — to “consolidate” people who used drugs in a single place by permitting sale and use in the park — quickly backfired. Many people who used in the park urgently required regular medical care, supplies, and housing. HIV infections and death rates climbed. While equipped bystanders stepped in to help supply clean needles and treat the injured, authorities shut down the park in response to political pressure. The resulting popup in Letten, located near a train station just across the river, was closed shortly thereafter. This was Switzerland’s first attempt to address the open drug scene, and it was without much of the success that has come to define Switzerland today.

The entrance to the city-run drug consumption room (DCR) in Zurich. This DCR is one of few in the world that permits micro-dealing, in a long-standing de facto agreement with local police.

Within a few years of worsening conditions in Platzspitz, Swiss officials shifted tactics. Instead of taking a punitive, prosecutorial approach, Switzerland chose to rise to the challenge, beginning with a strategic, scientifically informed shift toward harm reduction. This led to the development of Switzerland’s landmark Four Pillar Policy, a comprehensive approach encompassing harm reduction, treatment, prevention, and enforcement.

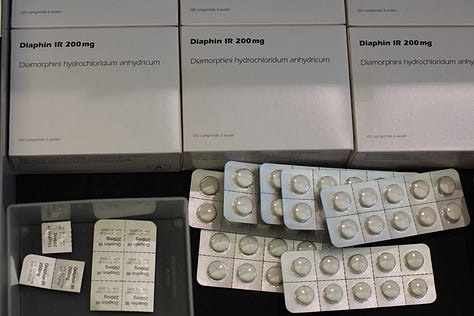

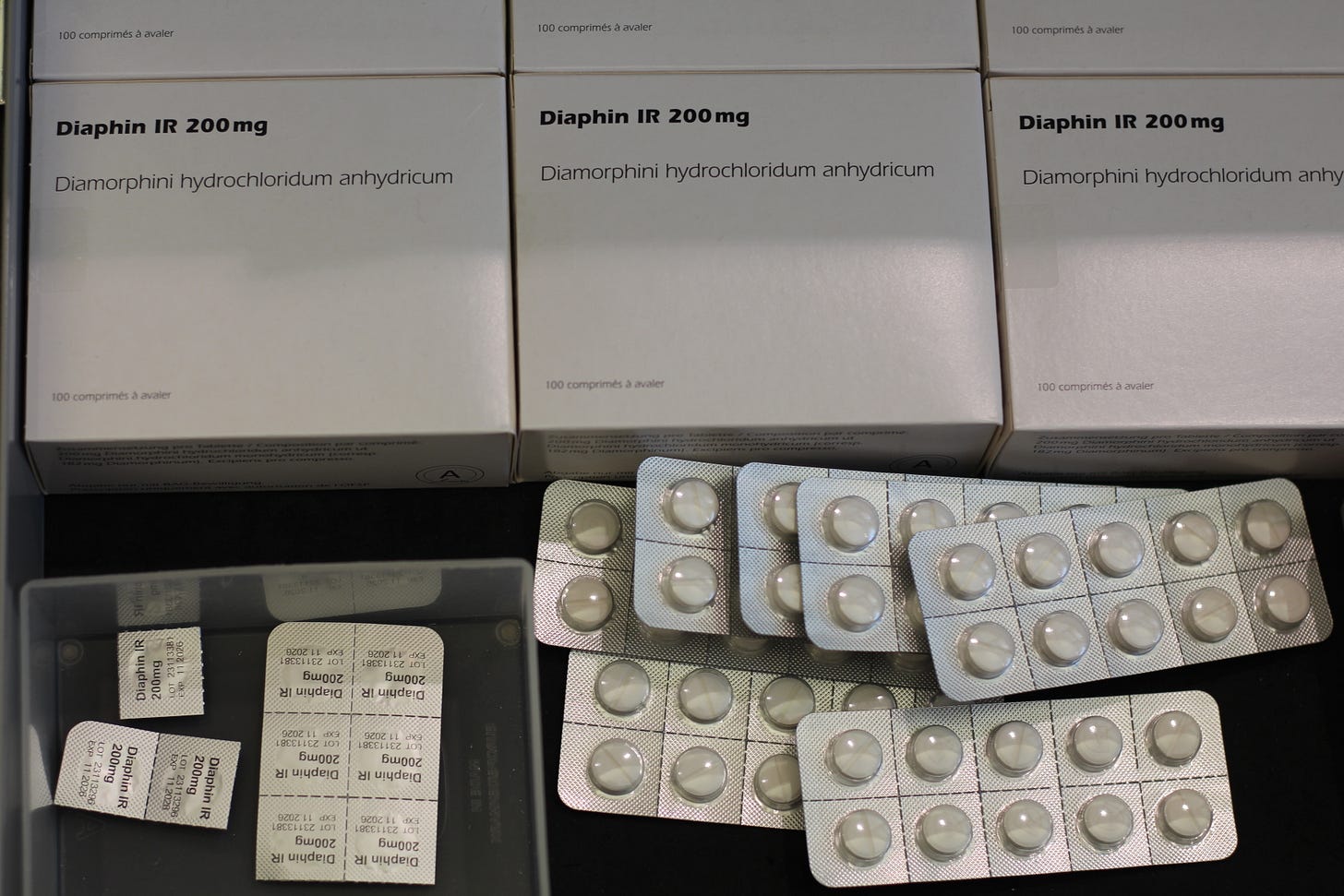

Developed in 1990 and codified in 2008 via the Narcotics Act, the four pillars emphasize the importance of improving the environment around drug use rather than punishment. The proposal paved the way for various initiatives that had a snowball effect across cantons — smaller administrative regions akin to U.S. states — including the world's first legal overdose prevention center, Contact Netz, in the Swiss capital, Bern. With the passage of these measures, legalized drug consumption rooms were able to provide safe, professionally supervised spaces where people could use pre-obtained drugs. Zurich opened its own consumption rooms, which still stand today. Even heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) facilities opened in the city, offering pharmaceutical-grade heroin (diacetylmorphine) for use in a medically supervised clinic setting, with the first program tested in Switzerland in 1994. Across the board, treatment options dramatically expanded.

Diamorphine is one of several medications provided to patients with substance use disorder. Switzerland is one of few countries to offer “heroin-assisted treatment” (HAT).

In Geneva, Premiere Ligne’s Quai 9 centre, which opened in 2001, was among those that found its footing as a harm reduction and overdose prevention center. Standing as a neon green shipping container-esque facility in the middle of the city, the nonprofit offers a safe and supervised place for people to inject, snort, or smoke drugs. The facility is open to all who register. As Jennifer Hasselgard-Rowe, Quai 9’s Scientific Director, remarks on the inspiration for the centre’s inception, “Every canton felt they needed to take care of [overdose]. In response to the rampant HIV epidemic, Quai 9 has worked to save lives and prevent transmission. “It was in response to a public health crisis and part of the creation of the four-pillar strategy — a combination of all [these factors],” Hasselgard-Rowe explained.

Social sanitary worker Tamara Chkheidze (left) and adjointe scientifique Jennifer Hasselgard-Rowe are instrumental to the operation of Premiere Ligne’s Quai 9, a harm reduction and overdose prevention centre in the heart of Geneva.

The most significant externality of the pillars is the absence of punishment, which otherwise tends to entrench individuals within a system that leaves them more vulnerable upon re-entry to society. Incarceration, the so-called “public safety strategy” of the United States, heightens overdose risk during and post-release. “Prohibition is the worst system to regulate,” remarks Thilo Beck, Co-Head of Psychiatry at the Arud Center for Addiction Medicine in Zurich, Switzerland, a nonprofit providing outpatient general medicine, psychiatry care, and the whole range of opioid agonist treatment (OAT) including HAT. “You have no influence, no control. So it’s the worst system, but [it’s] difficult for politicians to understand.” Arud offers some of the most extensive and personalized treatment options for individuals with substance use disorder, and all costs are covered by compulsory health insurance, according to the Swiss Health Insurance Act.

In Zurich, Thilo Beck is the co-Chief Psychiatrist at Arud Centre for Addiction Medicine, which runs an extensive multi-level treatment facility for substance use disorder.

Though met with its share of pushback, Swiss citizens overwhelmingly have supported the Four Pillars. A 1997 challenge to the proposal was crushed by a 70% approval rate, swiftly dismissing opposition efforts. Indeed, internal referenda have been crucial to Switzerland's approach to the overdose crisis, attributable to a political system allowing its cantons and individuals to demand change on essential issues.

When combined, the components of the four-pronged approach have paved the way for lower overdose rates and a sharp decline in crime by people who use drugs. The need for a similar approach is evident in the context of the United States. However, meaningful implementation is often labeled “impossible,” attributed to political gridlock and competing interests vying for supposedly limited local, state, and national resources.

Importantly, the Four Pillars are not a partisan issue. It would be a mistake to think that the strategy was only efficacious due to Switzerland's progressive politics – the country is notoriously conservative on social issues, with a right-shifting parliament. Instead, Switzerland's open-mindedness and patience – to allow centers the time to build capacity and introduce their services – allowed it to scale its treatment efforts, a necessary form of harm reduction.

Quai 9 has several designated areas for people to use substances safely and with supervision. Pictured above is the injection station and, situated separately, is a designated area for people to smoke.

Similarly, the “resource scarcity” argument in the U.S. presents a false trade-off. Countless studies illustrate that the current response to the overdose crisis is causing hospital systems to hemorrhage billions of dollars that could otherwise be reallocated to more effective initiatives. Many centers in Switzerland, such as the NGO Première Ligne, are entirely subsidized by the government. A foremost priority in the US must be to remove barriers so NGOs can set up prevention, treatment, and harm reduction centers that reach the people they aim to serve. This marks the first step toward a four-pillar approach, sparking a ripple effect that expands resource availability that transcends community borders.

Switzerland's story is clear: harm reduction and treatment works. No fatal overdose has ever been recorded at any overdose prevention center around the world. Today, Switzerland’s management has improved such that cantons can pinpoint the populations they aim to serve. As Florian Meyer, Division Head in the Department of Social Affairs in the City of Zurich, remarks, “We have this population of about 800-1000 people, and we know them. About 85% of them are citizens of Zurich. They are not anonymous.”

Florian Meyer is the Division Head of the Department of Social Affairs for the city of Zurich. He oversees several DCRs in the city, including this one on Selnau Straße.

An iron fist only prolongs and deepens the problem, exacerbating paranoia and stigma along the way. Embracing a four-pillar approach — or, at the very least, recognizing the failings of punitive measures — is essential to start reversing the damage wrought by years of crisis mismanagement in the U.S. and beyond.